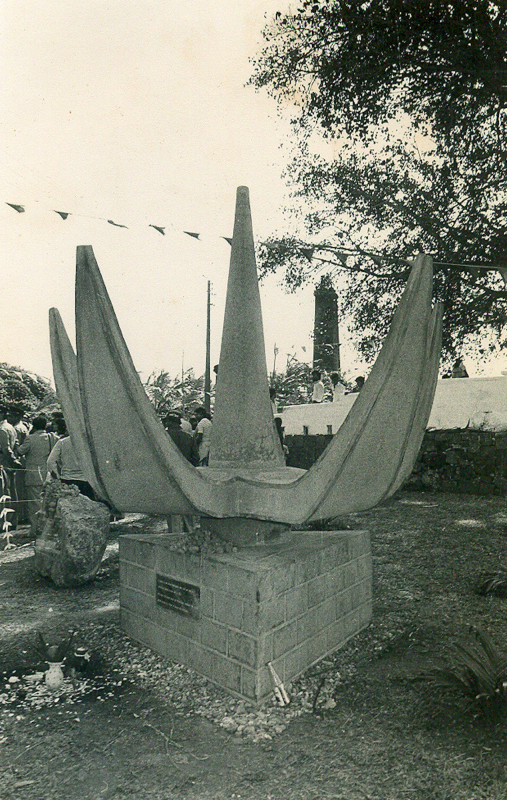

Sight of the site: Phooliyar

Today the monument in front of the Antoinette sugar estates in Phooliyar (Fig. 1) looks like a lotus. It is installed on a high raised pedestal. The inscribed commemorative text on the pedestal reads “A tribute to the Indian immigrants who first set foot as indentured labour on this sail in 1834. With their toll, sweat and blood they nurtured this island which today is heaven of peace and prosperity”. A metal plate fixed on the boulder at the foot of the monument displays the information on the artist and patrons of the monument. It states the following:

Today’s Mauritians salute their sacrifice perseverance and selflessness unveiled by the Prime Minister Mr. Aneerood Jugnauth on the 2nd September 1984, executed by Mala Chummun, with technical assistance from M.A Soobratty and J. Khirodhur on the occasion of the 150th anniversary celebrations of the coming of the Indian immigrants and abolition of slavery.

Fig. 1 – Phooliyar Monument, 2018

Courtesy author

The national flags of India and Mauritius fly well above the monument. A few small orange jhandas (religious pennants) that try in vain to reach the two national flags are tied on the trees. Next to the monument, a perpendicular stone plaque displays an image of the ship, Atlas. Under the image the inscription runs as follows: “Ship model on which indentured labour were brought to Mauritius and to other colonies; indentured labourers (36) who came on board the Atlas (1834).” The thirty-six labourers’ names appear underneath the inscription.1 At the foot of this commemorative tablet is another slab on which the inscription follows:

to honour the memory of the first indenture labourers who toiled and lived at Antoinette-Phooliyar in November 1830. This plaque was unveiled by Lady Sarojini Jugnauth in the presence of Hon. R. Yerrigadoo, Attorney General, Hon. S. Baboo, minister of Art and Culture, Hon S. Rutnah, Government Whip. and Mr. D.Y.D Dhuni, Chairperson of the Aapravasi Ghat Trust Fund, on 3rd April 2016.

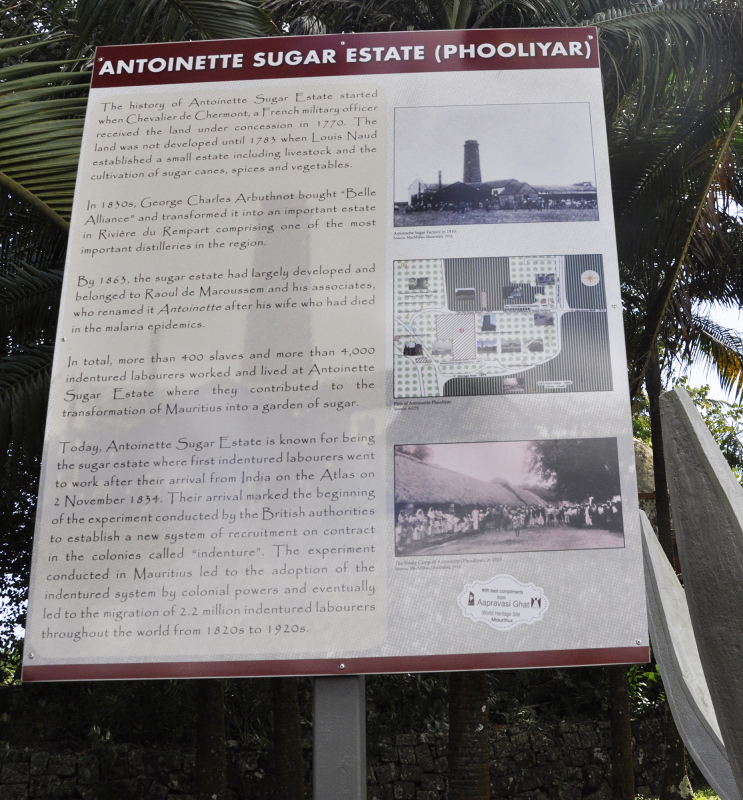

The Aapravasi ghat trust has put up a notice on the Antoinette sugar estate on the top at the front end of the monument. It gives a brief history of Antoinette sugar estate that goes back to 1770 when Chevalier de Chermont, a French military officer got the land at a discount price. In 1783 Louis Naud transformed the land into an estate to cultivate sugar cane, spices and vegetables. Georges Charles Arbuthnot developed it into a prominent estate with branded distilleries in the region of Riviere de Rempart by 1830s. In 1863 Raoul de Maroussem and his associates became the owners of the sugar estate. He renamed the estate in the memory of his wife, Antoinette who died early due to malaria. The last part of the board reads (Fig. 2)

In total, more than 400 slaves and more than 4000 indentured labourers worked and lived at Antoinette where they contributed to the transformation of Mauritius into garden of sugar. Today, Antoinette Sugar Estate is known for being the sugar estate where the first indentured labourers went to work after their arrival from India on the Atlas on 2 November 1834. Their arrival marked the beginning of the experiment conducted by the British authorities to establish a new system of recruitment on contract in colonies called “indenture”. The experiment conducted in Mauritius led to the adoption of the indenture system by colonial powers and eventually led to the migration of 2.2 million indentured labourers throughout the world from 1820s to 1920s.

Fig. 2 – The Information board, 2018

Courtesy author

This paper2 traces the process of the memorialization of migration, material and memory of the indenture labour system in Mauritius. It probes the visual elements of the site and sculpture in Phooliyar as a case study. I propose the site as a counter indenture that was constructed to authenticate not only the mobility of the indentured migrants, but also their descendants and the materiality of the indentured system. The site is a counter archive that gradually unfurls the complex narratives of migration of both the labourers and the following generations. The field research carried out between 2015 to 2018 has helped me to uncover various trajectories of the transformation of the inheritance of the indentured labour practice into the heritage. In the first part of the paper I describe the making of the site and the monument. I discuss how the Phooliyar resonates the emotion and imagination of the agencies that were engaged in executing the monument. It is an embodiment of the layered cartographical understanding of the land, island and nation-Mauritius of the artist, the government officials and the community. In the second half of the paper I argue that the “indenture process” was deployed to commemorate the history of migration, as well as the method of migration through the making of the site, Phooliyar.

“Stamping” the site and sight

In 19843 the Government of Mauritius decided to celebrate the one hundred and fifty years anniversary of the arrival of the Indentured Labourer4 through a series of events. The celebration5 was designed from the place where the first group6 of indentured labourers started working. Thus, the Antoinette sugar estate7 in the north east of Mauritius was visited physically and historically. The property was found to be part of the Mount Sugar Estate in a dilapidated condition. On the estate site the worn-out chimney with the date 1865 on it and a shrine like temple, popularly known as Kalimaye became a contact zone to trace the ancestors and those Mauritians who worked in the Antoinette sugar estate since 1834.8 However, the nearby site to Kalimaye where the monument stands today was cleaned to install the commemorative structure. Today, the site beside the road faces the paddies of sugar cane by keeping the temple-shrines at its back.

Mala Chummun was invited to sculpt a monument for this purpose. She was a young graduate from Santiniketan, the academic institute established by the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore in West Bengal state of India. She joined the School of fine arts, Mahatma Gandhi institute (MGI)9 in Mauritius in 1979. Mala mentioned that she was not confident about making a sculpture for a grand event like the celebration of indentured labour; she was young and knew very little about her family history as well as the indenture labour system. She informed10 that her parents were reluctant to speak about their family history in their childhood. They just knew that they are of Indian origin. When Mala and her siblings inquired they avoided speaking in detail. She mentioned that the offer of carving a memorial sculpture pushed her to reflect upon her knowledge production about the indentured labour and its difficult belongings.11 However, she decided to recast her identity through making a commemorative sculpture. Mala initially thought of simple forms of a figure. She was drawing a leaf of the Chaitm plant in those days to develop a figure out of it. She was fascinated with the seven spread of the Chaitm12 leaf clinging to a stem. However, the sculpture ultimately, she made bears some resemblance to a lotus from a distance because of its bloomy and petaloid forms clinging together. The memorial approximately three feet high and two feet wide looks simple; it is a rising form (Fig. 3). The descendants in Mauritius sometimes connected the five petaloids forms with their predecessors’ communities, such as Bhojpuri, Tamil, Telugu, Marathi and the Muslim communities as well as the five elements of nature like earth, water, fire, air, and metal.13 The long tubular form between the five petaloids is an enigmatic representation of the chimney of the sugar factory. Mala pointed out that it is the most significant and ambivalent aspect of the monument. The monument is made of cement in the cast and mould technique. The process of making the monument unfolds the “structure of feeling” where feeling and thought are not in counter relationship but rather ‘thought as felt and feeling as thought.’14 It is an area where belief system, institution and ideology are the experience of thought and feeling, but not an inherited articulation. It also belongs to the fluid consciousness of the people and their layers of living. Thus, it creates an embryonic relation between social and material.

Fig. 3 – Mala Chummun, artist with her work, 1983

Courtesy Mala Chummun

Stone as the material for making the monument was preferred by the committee; it is also locally available in Mauritius. Nonetheless, Mala chose cement instead of stone in spite of having skills in stone carving. Cement is the imported material in Mauritius.15 In other words, cement is a migrated material in Mauritius. Thus, Mala connected the material trade of cement with the indenture labour trade. Moreover, in the 1980s Mauritians were replacing their thatched houses and shops with concrete. Cement turned people’s material for the construction of the buildings in the 1980s.16 Mala reflected upon her training in the Tagorean school specifically under Ramkinkar Baij, the renowned sculptor of India. Her motivation of thinking through material for making the memorial monument in Phooliyar came from her teacher Ramkinkar Baj. Baij’s sculptures17, such as Santhal family (1938), Coolie mother (1943-44) and Mill call (1956) were her reference points. His processing of the material like cement and concrete was an aesthetic turn for Mala to reflect upon her entangled practice and temporal present with Phooliyar. Moreover, Baij’s critical intervention through the artistic practice on the issues of the displacement of the community (santhal) in the name of development, labour and land was a trigger for Mala to think through her feeling, and knowledge production. She altered the technique she learned in her graduate days. Since stone was much a desired material by the committee, she created stony effect on the surface of the monument. Hence the monument was not only the memorialisation of the journey of the indentured labourer but also a journey of their descendants and of materiality.

Sarita Boodhoo, one of the active members of the organising committee and the chairperson of the Bhojpuri speaking union at the Old Prison building in Port-Louis brought the offer to Mala. She apprised of Mala’s struggle during those days financially as well as conceptually to carve her identity in Mauritius after returning from India. This project brought them closer and they shared an extraordinary togetherness following years.18 However, it was the time Mala turned to the archive of The Folk museum of Indian immigration and Indian immigration Archives in the Mahatma Gandhi institute to trace about her migrant forefather. Simultaneously she sat beside her mother and listened her memories and the stories of her great-grandfather Chumum who came to Mauritius on 4th June 1859. Her old mother and the grown-up daughter’s conversations encouraged the daughter (Mala) to find out more about him in the houses. She found her great-grandfather’s wooden trunk as abandoned in a broken condition from the scrap store of her ancestor’s house. He came with the trunk from India. She repaired it. She mentioned about her dexterous hands in woodcarving; touching, rubbing, and nailing are part of woodcarving. However, doing those to repair the box was an entirely different feeling, as if she was touching the mark of a dried wound that appeared on the body with a roughness beside the softer skin, thickening black beside tender brown. However, once she repaired it, the discarded box became an ancestral property.

It went to her mother’s brother; hence another journey of the trunk began. Thus, the commission of the monument not only made Mala commute every day from her house in Port Louis to Phooliyar, but also down memory lane with her mother, siblings, and kin. It opened up ways to live and deal with difficult and fragmented family histories. It also directed her practice and contribution in the institution (MGI) in the following years. She hired two labourers from the sugar estate as assistants, instead of any student from the Fine Arts department in MGI. Mala informed that she had to train them to assist her, as they did not have any skill and knowledge of casting and moulding sculpture. She linked them with labour.19 Mala’s deliberation was to establish a connection with the present sugar estate workers, and make them one of the stakeholders of the heritage memorial which was a part of the nation building project. Thus, it was not only to establish the representative relation with the past, but also to build a thread of the formation of the republican government in 1992. She made sure their names appeared along with her at the foot of the monument. Mala used the making of the monument as ‘medium’ to re-imagine the ‘imagined community’ of the past and following years in her country. Here, I suggest ‘medium’ the way Rosalind Krauss argued for the materiality of artistic practice as medium. Rosalind Krauss writes “in order to sustain artistic practice, a medium must be a supporting structure, generative of a set of convention, some of which, in assuming the medium itself as their subject, will be wholly ‘specific’ to it, thus producing as experience of their own necessity”.20

Here I also refere to the idea of Benedict Anderson’s “imagined community” where he argued that the imagined community morphed to set the political boundaries of modern nation. The formation of imagined community occurred in convergence with capitalism and print culture that embraced and mobilised the vernacular language gradually, unselfconsciously and pragmatic way. Thus, it gave rise to linguistic nationalism.21 Here, I depart. I try to argue that the vernacular aural and oral culture was responsible of forming the ‘imagined community’ in Mauritius rather the print market. The level of literacy amongst the indentured migrants was low.22 Simultaneously the pattern of surveillance left limited options for the dissemination and the circulation of the vernacular prints in the island.23 On the other hand, the locus of baitka was orality and auditory that gradually formed and mobilised the collective consciousness. It became the space for educational training the following generation. Here, I also suggest that the sonic culture of the migrant labourers had empowered the imagination of the new community (girmitya). For example, in 1943, the official report stated that

The police officers could not speak directly to the crowd. They did not understand what the crowd were shouting. Interpreters were necessary. The senior police officers hardly knew what a baitka was. They could not be certain whether the people assembled, or some of them, were praying or not. In short, they were unfamiliar with the language, religion and customs of people whom they wished to persuade and perhaps coerce.24

The word “girmitya” itself is a construct of sonic derivation and distortion of the “agreement” (indenture). What I argue is that aural distortion opened up a way to imagine a new community through the name “girmitiya” that fought to form the government in 1968. The indenture labour document was just an object and picture to them as very few could decipher the agreement. Nevertheless, it was perceived through the pronunciation of the word ‘agreement’ that created “girmit”.

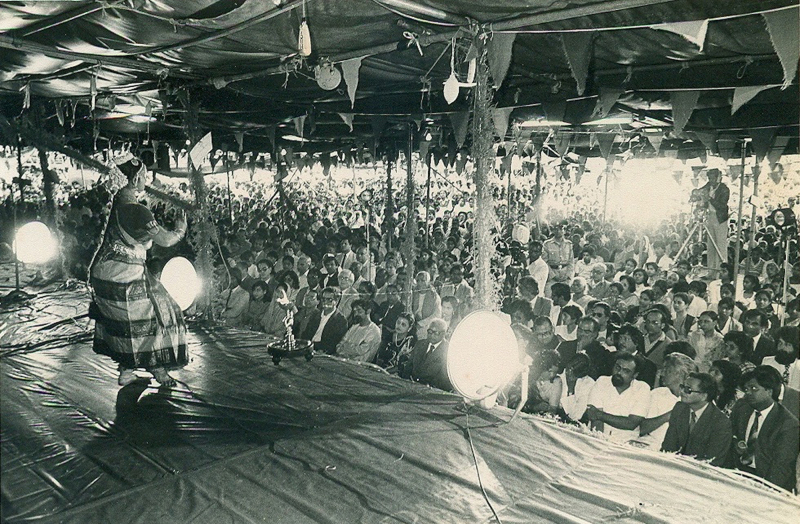

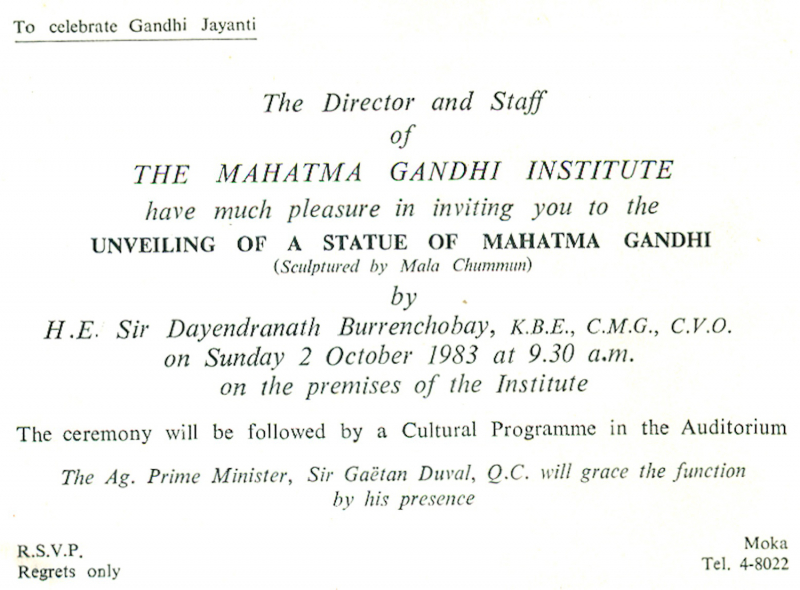

A weeklong cultural program, events, and fair on the site was organised on the occasion of the inauguration of the memorial on 2nd September 1984 (Fig. 4, 5, 6 & 7). It included tree plantation and recreation of the ‘remembered and imagined village life of indentured labours in Mauritius as well as in India’. The people performed in dressed up costume, jewellery and make-up and enacted the activities such as cultivation of paddy, rearing and milking cows, making of huts, villages sports (kabaddi, kite flying) and marriage ceremony. In the evening, there were additional cultural events performed by the different the linguistic groups such those speaking Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, Urdu, Bhojpuri and Hindi as well as local Creole saga singers. The cultural troupes from Senegal and Mozambique also performed. Bullock carts were arranged to take the people around to popularise the site. People who were observers of the events told me that it was like India’s village fair, which does not happen in Mauritius. However, an acharya from the Mauritius sanatan dharma temple federation was invited to chant during the time of ceremony. It indicated the site for the Hindu pilgrims and connected with all the associations of Hindu activists in Mauritius. Thus, the maintenance of the site becomes an agenda of those associations.25 The workers of one of those associations installed the orange jhandas that fly almost at the same height of Mauritius and Indian flag today (Fig. 1).

Fig. 4 – The Inauguration ceremony, 2nd September 1983

Courtesy Mala Chummun

Fig. 5 – Gathering on the inauguration day, 2nd September 1983

Courtesy Mala Chummun

Fig. 6 – A dance performance in the evening celebration, 1983

Courtesy Mala Chummun

Fig. 7 – A circular of Mahatama Gandhi Institute, Celebration continued, 1983

Courtesy Mala Chummun

However, the place was popularly known as Antoinette sugar estate in Riviere de Rempart. But after the installation of the monument and the celebration, the name Phooliyar name was marked as a site and sight of the nation in1984. It perpetuated the Aapravasi ghat trust to include its name when they put up the information board on the Antoinette sugar estate in 2016. Though Phooliyar village does not exist. Many from the old camp of the sugar estate settled opposite to the Royal road. The village council had named the new settlement as Phooliyar nagar, shortly after the event.26 Phooliyar is the distorted sonic version of Pillayar in the Bhojpuri idiolect. It means Ganesh (a God) in Tamil language. When they started calling the camp as “Phooliyar” nobody could narrate that. A few Bhojpuri speaking Mauritians27 narrated what their ancestors had told them. Pillayar would appear in their Tamil cohorts’ conversation, which they barely understood; they could grasp the word that appeared frequently. Pillayar, which was heard as Phooliyar was one of those. I suggest that Phooliyar may be a derivative of Pulayas (Puller), Tamil indentured labourer who came to Mauritius along with others in 1830s.28 However, the Tamil migrants either used to address the temple as Pillayar (in the name of Ganesh) or called themselves Pulayas. The Bhojpuri workers preferred to use in their idiolects instead of those used on the Antoinette sugar estates. Thus, today’s Phooliyar is an aural and tongue twisted version of either Pillayar /Pulayas. It was constructed as voice and claim of the descendent indentured labourers of Mauritius to such an extent that they stamped the Antoinette sugar estate by the monument as Phooliyar. Furthermore, the bell of the Antoinette sugar estate is today kept at the entrance of the Tamil temple in Petite Julie on request of the Tamil community.29 Here the bell is not only the property of the sugar estate but also a stamp of time, sound and schedule of the workers in the estate.30 The community appropriated it in the temple like “a trophy of war”.31

Thinking through “indenture as process”

The indenture is derived from Endenter, a French word that means to jag or notch and connotes “writing”.32 In other words, the indenture is a writing that contains a contract. It also suggests two copies that are written side-by-side on the same paper and later, are cut off from each other in toothed or jagged line. Each party gets a piece of the agreement. The jagged edges of the paper that fit together are the proof of authenticity of the document.33 In the part of the Vade, Mecum Sammuel Richarson suggests it as much more than material evidence of the relationship between two parties and almost like moral guide, though he hardly writes about its concept and practice. However, the indentures are the text and signature and also an evidence of the relationship that extended and explored further to materialise and mechanise indenture labour.34 Furthermore, “stamping” is another way of authentication the indenture.35

The penal tattooing practiced from 1749 to 1849 in Bengal and Madras was called godna. It appears with names of the persons and crimes and dates of the verdicts on the foreheads of the convicts36. Moreover, the practice of drawing godna /godhana on the body was widespread among the communities in India for various social purposes, such marriage, childbirth, health care.37 However, Clare Andersons argued that godna on the convicts foreheads provided the idea of stamping on the foreheads of the immigrant labouerers as an identification mark. 38Arthur Payne’s report reveals that after the final inspection the foreheads of the selected migrant were stamped ‘with figure which is not easily imitated.’ It was verified next day to ensure the fool proof selection of the migrant labour before they embark upon their journey to Mauritius.39 Anderson pointed out that the record keeping system of the ship later replaced ‘stamping on the fore head’. She draws an interesting connection between indent, and indenture through stamping or impressing and splitting or joining.40

Apart from stamping on the forehead, and godna, the Indenture Labour ID photograph was another visual indent that was introduced in 1864. Kathleen Harrington-Watt wrote that these photographs were used as visual verification documents to control the mobility of the migrants in Mauritius.41 The migrants, both old and new were systematically photographed from 1864 to 1914. The photographs were compulsory to be attached to the immigration tickets. The photograph was treated as counter visual indent to stamp the immigration ticket.42 The migrants had to give thumb impression in the agreement, which acted like notch of the validity from their side. Here, I add that the image and impression in various visual forms such as stamping on the forehead, godna, and labour id photograph are treated as indenture for the migrants from their recruitment to retirement or death. The bodies were also treated as indenture where visual mark on their forehead and Id Photograph appropriated as stamping. Later, the descendants also use the Indenture Labour ID photographs as the visual indenture to prove their indenture descent more than tracing their kin in India.

I further argue that the installation process and period of the Phooliyar monument from 1983 to 2016 are part of the counter indenting process. Their godna, girmitiya and formation of the government are the counter part of each other. These are historical indentations embedded in the history of nation building, reformation and distribution of land in the island since 1968. Thus, construction of the Phooliyar site is like stamping the landscape to make it indentured entity of the nation. Each visual and textual element in the site today is the indents to appropriate the historicity of the process of the indenture labour system. Let me return to the site from where I began this article.

The photograph of the monument with chimney behind from the artist’s personal album (Fig. 8) shows that the chimney of the sugar factory was visible from the site of the monument. The artist also aligned the cylindrical form of the monument with the chimney. The photograph was placed in her personal album as a visual record. Thus, she deployed the indenture as a process that involves splitting, joining and stamping as well by legitimising the visible. First, she replicated the form from her drawings of the chimney; then she composed it in-between the petal forms and create an illusion of a blooming floral sculpture; after that it visually jagged through photograph. Her desire was to create an impression of the chimney of the sugar factory not only through the monument, but also through the photographs. Mala explored the visual reasoning of photography that she learned from the history of indenture labour photo as well as her academic training at the art schools.

Fig. 8 – Phooliyar Monument with the view of the chimney of Antoinette sugar estate 1983

Courtesy Mala Chummun

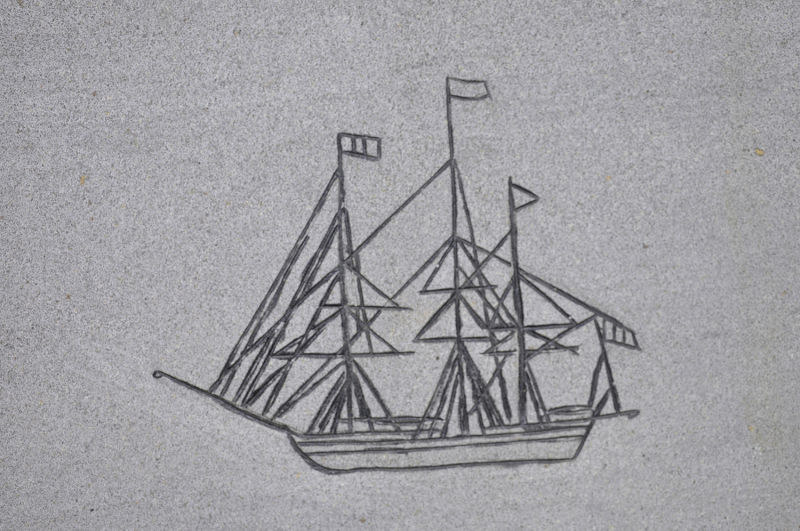

Today, the chimney has been overshadowed by the changing landscape; hence it is no longer visible from the site of Phooliyar monument. Interestingly another image of the chimney of the Antoinette sugar mill in the picture of the information board appears in the site (Fig. 2). It appears to endorse the visual indenture of Phooliyar memorial. The Aapravasi Ghat Trust installed the information board on Antoinette sugar mill and memorial plaque (Fig. 2) in 2016 almost after two decades of the installation of the sculpture. It has been put up at the same height of the sculpture. The memorial plaque is next to the sculpture, but not of the same height. The fencing around the plaque encourages one wonder why it needs fenced protection and from whom. The text in the plaque starts with a figure of a ship inscribed on it (Fig. 9). The process of inscribing on the stone is like tattooing on the stone. The names of the migrants, and their arrival information in cursive letters appear below the image of the ship; but the rest of the text, such as the names of the Government officials, the dates and the purpose of their presence in that site is in capital letters. These are not just designs, but decisions as well. The decisions were laid to mark and stamp the site of Antoinette sugar estate as Phooliyar.

Fig. 9 – Impression of the ship Atlas, Commemorative Plaque, 2018

Courtesy author