The objective of this paper is to demonstrate how the Hindi film Photograph (2019), written and directed by Ritesh Batra, employs various resources to create moments of silence that enhance aesthetic pleasure and enable viewers to contribute to the narrative. The film commences with soft music accompanied by everyday noise such as honking in the street, the snoring of people sleeping in a room, the creaking of a fan, the rattling of a train, and the clicking of a camera. Given that Mumbai is the commercial capital of India, this opening sequence evokes a sense of embarking on a journey into the heart of loudness. Another Hindi film that brings to the fore the noise issue in the city is Shor (1972), written, produced, and directed by Manoj Kumar. Its opening credits, which span approximately 4 minutes, feature nothing but daily noises of all kinds.

Max Picard, the renowned Swiss philosopher, aptly observes: “The great cities are like enormous reservoirs of noise. Noise is manufactured in the city, just as goods are manufactured.”1 This statement raises questions about whether we are particularly drawn to the noise in the film Photograph, due to the subtitles that indicate each sound or whether noise is prevalent throughout the film. This noise in the opening sequence serves as a counterpoint to the silence that dominates the rest of the film.

But what is silence and how do we understand it? After having discussed the subject throughout his book, George Prochnik finds in the end a peculiar relation between sound and quiet: “… if I were to hazard a definition of silence, I would describe it as the particular equilibrium of sound and quiet that catalyzes our power of perception.”2 Therefore, silence is the outcome of a balance between sound and quiet that enhances our perception, allowing us to see or experience what would have been lost otherwise. Furthermore, we can only comprehend silence when we juxtapose it with sound. Max Picard views the silence of the modern world as a mere interruption of the continuity of noise, which is precisely how the film Photograph portrays it:

In the modern world language is far from both worlds of silence. It springs from noise and vanquishes in noise. Silence is today no longer an autonomous world of its own; it is simply the place into which noise has not yet penetrated. It is a mere interruption of the continuity of noise, like a technical hitch in the noise-machine – that is what silence is today: the momentary breakdown of noise.3

This passage draws our attention to the spatial and temporal dimensions of silence. The silence of ancient times differs from that of the modern world, and the silence of the countryside is distinct from that of the city. This film can be viewed as a technical hitch in the noise machine that produces daily noises such as the whirring of the printer, the sizzling of food, the ringing of the bell, and the squealing of brakes. Max Picard views human life as a journey from the world of originary silence, which is the prenatal phase, to terminal silence, which is death.

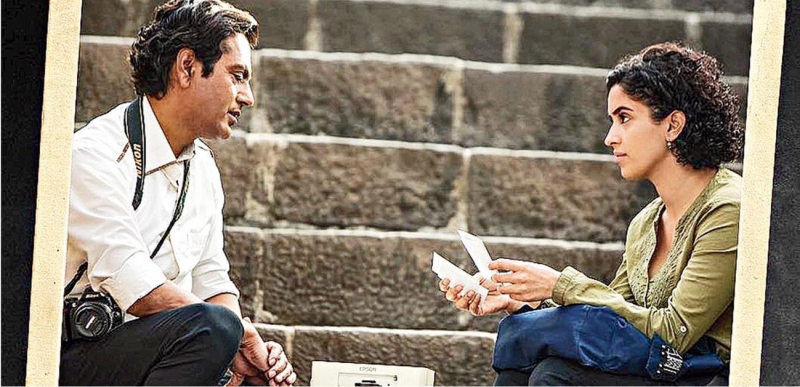

Silence should not be construed as a mere absence of noise in the film. Although non-diegetic sound is present throughout, the camera handling is more interested in suggesting than showing. Introverted protagonists like Rafiullah (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) and Miloni Shah (Sanya Malhotra) have such an affinity with silence that they communicate without speaking much and dialogue is absent for prolonged periods producing certain silence for the spectators. Gaps in the narrative invite active participation from the audience to construct the meaning. At times, the camera focuses on body language, questions are left unanswered and sentences are left incomplete.

This paper posits that silence is the medium through which both male and female protagonists of the film recreate themselves to engage with each other. They practice silence as a contemplative activity that engenders a deeper consciousness of the environment and connects them to the world in a new way. Paul Goodman, the literary and social critic, identifies nine types of silence:

There is the dumb silence of slumber or apathy; the sober silence that goes with a solemn animal face; the fertile silence of awareness, pasturing the soul, whence emerge new thoughts; the alive silence of alert perception, ready to say, “This… this…”; the musical silence that accompanies absorbed activity; the silence of listening to another speak, catching the drift and helping him being clear; the noisy silence of resentment and self-recrimination, loud with sub-vocal speech but sullen to say it; baffled silence; the silence of peaceful accord with other persons or communion with the cosmos.4

This paper will refer to and study some of these types of silence in the film Photograph.

Unsaid and Unfinished

The photograph serves as a metaphor for silence in the film, and the photographer is portrayed as a lover of silence. Rafi, the male protagonist, is a street photographer by profession who captures images of tourists visiting the Gateway of India. While photographing his customers, he recites lines which he must have memorized as he repeats them in another sequence: “सालों बाद जब आप ये फोटो देखेंगे तो आपको आपके चेहरे पे यही धूप दिखाई देगी। … आपके बालों में ये हवा और आपके कानों में ये हज़ारों लोगों की आवाज़ें। … सब चले जाएँगे। हमेशा के लिए सब चले जाएँगे।”, Subtitles provided for non-Hindi speakers read as follows: “Years from now, when you look at this photo, you’ll feel the sun on your face … this wind in your hair and hear all these voices again. Or it will all be gone. Gone forever.” In the original Hindi version, ellipses are used to indicate pauses taken in the middle of the monologue. These pauses allow for an alternative translation: “Years from now, when you look at this photo, you’ll feel the sun on your face. … This wind in your hair and these voices of thousands of people in your ears … All will be gone. Gone forever.” The initial translation as presented in the film’s subtitles suggests that capturing the present moment in a photograph will enable one to recollect the sun, wind, and the voices of the people again. Otherwise, these elements will be lost forever. The second translation, which I propose, posits that while one can capture the sun in a photograph, the wind and the voices of the people will dissipate. In other words, photographs can capture light but not sound. Consequently, only silence remains. John Biguenet discusses the camera and photography as follows:

A camera is a silencer: the photograph is a glimpse of the world with all the sound leached out. Yes, in a cropped image of an arm, we go on to imagine its hand, and so we fill in the photograph’s silence with the chatter, the chirping birdsong, the distant motors, the riffling breeze that our mind insists upon for us to make sense of the puddles of colors, the variegated shadows staining the white paper as, somehow, a fragment of the lived moment. But unlike light, sound does not leave its imprint on the photograph.5

To better comprehend the statement above, we can compare a video recording which captures both sound and light, and a photograph which allows only light to leave its imprint and eliminates the sound. The first photograph of Miloni will be appreciated by her in silence and her multiple photographs will be preserved by Rafi to be admired by him in privacy, away from the gaze of others. If we accept Alain Corbin’s assertion that the painting in the past was “words of silence” or “parole de silence”6, then we can say that in our age, the photograph also represents “parole de silence”.

The film leaves certain questions unanswered but the viewer can gain clarity by making connections between different sequences. Rafi expresses his reluctance to marry and advises his photographer friend to avoid marriage as well. When asked for the reason, Rafi tells him that he will become a softie like Zakir Bhai (Saharsh Kumar Shukla). Although Rafi doesn’t elaborate on how Zakir Bhai is like a softie, the viewer can infer from the explanation of a softie given by the lady at the counter as a type of ice cream similar to kulfi but not as hard. The viewer gains a better understanding when someone tells Zakir Bhai that he becomes too emotional while narrating the old story of a resident who committed suicide. This implies that Rafi is not very emotional and is uninterested in romantic relationships or marriage. During his conversation with Zakir Bhai, Rafi reiterates that he is tough like kulfi and not a softie like him. When Zakir Bhai asks what a softie is, the camera cuts to another scene without providing an answer. As the narrative progresses, Rafi’s initial claim is contradicted. Subsequently, the boy who previously sold kulfi plans to establish a softie business. This development serves as an indication that Rafi is now in love and intends to pursue a long-term relationship with Miloni. In other words, his kulfi-like personality is transforming into a softie-like one, contrary to his earlier assertion. He begins to use expensive cream and combs his hair more frequently to appear more presentable. In the following sequence, we observe him in a contemplative state as he searches for Campa Cola to please Miloni. The soft music accompanying this scene conveys his thoughts about Miloni. When Rafi is questioned about his habit of eating kulfi only at the end of the month, he begins to respond with: “My father, when he was alive…” but is interrupted by Gafoor Bhai, a shopkeeper who is familiar with him. The answer to this question is revealed later in the film during Rafi’s conversation with Miloni in a restaurant while they are having tea. Rafi explains that his father used to treat him with kulfi at the end of each month, and this ritual has continued since then. Gafoor Bhai, the shopkeeper, inquires about Rafi’s preference for a bride, but the question remains unanswered as Rafi departs, leaving the audience to speculate.

The film features several scenes that conclude with unresolved questions. Although Rafi writes to his grandmother that he has found a suitable partner for marriage, he has only recently met her and is not well-acquainted with her. When Rafi’s photographer friend inquires about how he will handle the situation when his grandmother (Farrukh Jaffar) arrives, the camera cuts to a classroom scene where Miloni is contemplating her photograph. The absence of a response amplifies our curiosity. However, as the thickness of silence becomes more pronounced, it occasionally gives way to speech.

Max Picard posits: “Speech came out of silence, out of the fullness of silence. The fullness of silence would have exploded if it had not been able to flow out into speech.”7 In the film, we can observe how beautifully the ice is broken. For instance, in an introductory scene in a taxi, Rafi informs Miloni that he has two elder sisters but he doesn’t inquire about her family. Miloni then informs him on her own, after a pause, that she too has an older sister. This exchange highlights how conversations can include not only questions without answers but also answers without questions. Later, after Miloni’s encounter with her teacher, Anmol Sir, on the pavement, Miloni tries to find out whether Rafi is fine. Rafi replies in the affirmative but doesn’t inquire about her well-being in return. We may infer that he is still preoccupied with Miloni’s encounter with Anmol Sir and forgets to find out how she is. Just after this moment, Rafi gives vent to his feelings and admits how he felt when he saw the teacher touching Miloni’s body. After a pause, Miloni makes it known that she is also fine as if she were replying to an unheard question.

The narrative of Tiwari’s (Vijay Raj) suicide is recounted by Zakir Bhai who emphasizes that Tiwari’s death is shrouded in absolute silence due to the absence of a suicide note. Still, he hears Tiwari’s voice through the rotating fan and his movements around the room at night. On a sleepless night, Rafi encounters a stranger in his room and inquires whether he is the ghost of Tiwari. However, the ghost requests a beedi to smoke instead. By this point, we have already heard the story of Tiwari’s ghost from Zakir Bhai, rendering Rafi’s question redundant. While smoking on the balcony, Rafi asks the ghost of Tiwari: Yaad aati hai? Because of the typical Hindi syntax which does away with the object, it is unclear whether Rafi is referring to someone or something: “Do you miss her?” or “Do you miss it?” The first one may refer to his beloved and the second one to beedi. However, the English subtitle appears as: “Do you miss it?”, thereby excluding another meaning. Hindi viewers will find ambiguity here whereas those relying on subtitles will miss it. Instead of saying something in response, Tiwari queries in return: “beedi?” He then proceeds to answer without waiting for confirmation from Rafi that he doesn’t miss beedi. Even if Tiwari mentions beedi, by now, spectators know that Rafi wants to know whether he misses the girl he loved. It is evident from the context that even Tiwari means “girl” though he uses the word “beedi”. This intentional misunderstanding on Tiwari’s part creates a beautiful effect. After a transitional pause, Tiwari’s ghost and Rafi express simultaneously their desire to start a Campa Cola factory and look at each other. This indicates that Rafi wishes to improve his financial situation so that he can provide Miloni with a life as comfortable as she has in her family now. Besides, Miloni enjoyed Campa Cola as a child and stopped drinking it only after her grandfather’s death; he used to treat her with it. The supernatural element in the form of Tiwari’s ghost serves as a valuable dramatic device in the film.

Ironically, only a ghost can give ultimate advice, as he has lived his life. In our lives, we experience existential anguish when we must choose between options at every turn. When we make a choice, we are uncertain about its consequences and whether it will prove to be correct. The film provides a hint that Rafi should avoid making the same mistake as Tiwari to prevent this love story from ending in tragedy. The film often includes pauses between two utterances, which invite us to form our hypothesis. Sometimes, the narrative provides some clues that confirm our hypotheses, while at other times, we are left without any, free to fill in the gaps.

Image 1

The Telegraph, 15 March, 2019

Narrative Silence

Rafi has been contemplating the girl he had photographed at the Gateway of India. One day, while gazing out from the bus, he observes something and begins to smile. A piece of soft non-diegetic music plays in the background and he disembarks from the bus. The scene is intriguing because the camera doesn’t reveal what he sees outside; we only see his smile and hear the music. As Paul Goodman suggests “Subtile feelings may have to be said in music.”8 If viewers recall the scene where Miloni’s father proudly clicks a picture of his daughter on a hoarding, they can guess what Rafi sees. Otherwise, they will have to wait until Rafi arrives near the gate of the coaching centre where the camera explicitly displays Miloni’s crowned image. In another sequence, Rafi is seated behind Miloni on the bus and greets her in a very soft voice. It is unclear whether Miloni hears him or not because there is no reaction from her. She looks back when the lady sitting beside her departs and then shifts towards the window, which is an inviting gesture. Pressured by his grandmother to marry, Rafiullah convinces Miloni to pose as his girlfriend before his grandmother. However, it is unclear how he has gone about it because that part is not shown to us. It is not clear whether she accepted because she likes acting or because she has begun to like Rafi. When the grandmother asks Rafi to show his friends his famous “crooked smile” inherited from his grandfather, the camera doesn’t focus on Rafi’s face but on his friends laughing. It leaves the spectator who may have been inattentive to his smile now both frustrated and alert. When Rafi and Miloni are having soft drinks with the grandmother, the camera focuses on the nervous agitation of Miloni’s feet. We see similar jerky movements when she has dinner with her family after Rampyaari (Geetanjali Kulkarni), a full-time maid in her house, has seen her on the beach with Rafi. Miloni is worried that Rampyaari might have told her parents about the incident. As sound ceases, gestures come to the fore. As George Prochnik states; “Even a very brief reduction in stimulus from one sense can trigger a heightened perceptual rush in another”.9 Again, Rampyaari says that the boy she is going to see at the request of her parents was fat and may become fat again. So, she helps Miloni find an excuse for rejecting the boy chosen by her parents. But the director does it in a very subtle way. When Rafi finally thanks Miloni for meeting his grandmother and is going to see her off, it seems that it is the end of this story. We don’t hear Miloni telling Rafi directly that she will not come again but she asks what he will tell his grandmother to which Rafi answers that he will handle the matter. But before taking the taxi, Miloni asks him whether he can take more snaps of her. This is a very subtle and beautiful way of saying that they will continue seeing each other. Since she has received a gift of an anklet from Rafi’s grandmother, she shows an interest in Rampyaari’s own anklet and her village, an indication of her wish to acquaint herself with a lifestyle awaiting her. Later, in her meeting with the son of her father’s friend, she reveals that she would like to live in a village. This may also be interpreted as an attempt on her part to bridge the class gap between them.

The film subtly portrays class and religious issues. In one scene, the taxi driver asks Rafi whether he works in a drama company because he finds it odd that they should be together, given their different classes. Rafi’s grandmother thinks that he would have been a compounder, a pharmacist who assists a doctor, had he not left his studies. Miloni, the daughter of middle-class parents, is studying to be a Chartered Accountant (CA) which will provide her with an attractive salary package. A visibly embarrassed Rafi tries to stop his grandmother from referring to his lack of education and abysmal economic status. We learn that he had been thrown out of school, along with his sisters, because of non-payment of fees. When Miloni is sitting with Rafi in the movie theatre, she is visibly disturbed by a rat scurrying under her seat whereas Rafi is not bothered and tries to assuage her feelings. Miloni is not used to watching films in such rat-infested theatres. Nor is she used to eating cheap street food as she gets a gastro problem after having eaten ice candy at the request of Rafi’s grandmother. The theatre sequence is repeated at the end of the film. Then, we discover that what we had seen in the middle of the story was not the complete sequence. It’s a beautiful experiment. When the sequence is repeated, we see it till the end this time. Miloni had come out in the middle of the film and sat in the corridor. Rafi joined her soon and they discussed the film. Though Rafi had not seen the film he anticipated an objection from the parents of the girl in the film as the boy is a simple mechanic. His case is not very different. So, they are left with the challenge to continue their relationship. The love story between Miloni and Rafi ends on an ambiguous note, leaving spectators without any explicit idea about their future.

Despite their differences in age, class, and religion, both protagonists are attempting to bridge the gap between them, albeit hesitatingly. Miloni is willing to assume a Muslim name like Noorie and lies to the grandmother that she is living in a women's hostel after having lost her parents. She also talks to Rampyaari, her domestic help, to learn about rural life. This could be an indirect way of conveying her interest in Rafi’s life, who hails from Ballia.10 Similarly, Rafi is trying to climb the social ladder to match Miloni’s status and agrees to start a factory at his grandmother’s request.

Protagonists in Pursuit of Silence

The 1997 Sinhala film, directed by Prasanna Vithanage, Death on a Full Moon Day, portrays the life of Vannihamy (Joe Abeywickrama), an elderly visually challenged man who refuses to accept that his son has died in the war. He has only a couple of lines to deliver throughout. The film employs extended pauses and is set in a village where the only sources of noise are the wind, rain, and the motorcycle of a government employee. In contrast, Shor, the Hindi film mentioned above is set in a metropolitan city. It features a protagonist who detests all forms of noise in the world due to his son’s loss of voice in an accident. Since he cannot hear his son speak, he avoids any sound that reminds him of his son’s disability. In this film, noise is juxtaposed against muteness rather than silence. Bernard P. Dauenhauer aptly remarks: “The difference between muteness and silence is comparable to the difference between being without sight and having one’s eyes closed.”11 What is pitted against the noise in Photograph is not an inability to speak, a deficiency to be overcome but quietness as a choice. Miloni and Rafi distinguish themselves by their longing for silence in a world that relies on verbal inflation. Both are introverts, though Miloni is more soft-spoken and reticent, ever transferring her inner silence to her surroundings. We see her at the dining table eating quietly and occasionally giving monosyllabic answers to the questions before falling into silence. Be it hesitation or prolonged reflection, both the protagonists speak less and think more. Most of the time, we are left to speculate about what is going on in their minds. As Max Picard says: “Sometimes in conversation a man holds something back inside himself, he does not allow it to come out in words; it is as though he feels he must keep back something that really belongs to silence.”12 It is the photograph of Miloni which gives a fillip to the plot. She is caught contemplating her photograph in the class and the teacher seizes it. She then tries unsuccessfully to get another good photograph at the Gateway of India from another photographer. We have no clue as to what is captivating in her photograph as we never see it clearly from the front. It is a photograph that exercises an irresistible charm of the unseen. In a later sequence, when she is on the boat with Rafi and the grandmother, she reveals that she found her other self in the photograph, a girl who was happier and prettier. Another photograph of hers is pitted against this one. That is her photograph with a crown on the billboard of the coaching centre presenting her as the topper of the Chartered Accountant (CA) foundation course. We see her father in the opening sequence clicking that image proudly with his mobile and telling his friend that his younger daughter, Miloni, is preparing for CA Inter. This picture tells a lot about the daughter realizing the dream of her aspirational father. Max Picard says aptly:

Images are silent, but they speak in silence. They are a silent language. They are a station on the way from silence to language. They stand on the frontier where silence and language face each other closer than anywhere else, but the tension between them is resolved by beauty.13

The two photographs of Miloni depict two contrasting worldviews. One is Miloni’s own which is gradually taking shape, and the other is the vision imposed on her by her family, which she has been quietly accepting until now. In one scene, we see her mother and sister deciding the colour of her dress and Miloni agrees nonchalantly. Later on, she won’t be able to tell the colour of her choice when she is asked by Rafi’s grandmother. We are told that she had been receiving trophies for her amazing acting skills in school, but her mother requested that teachers stop awarding her so that she could concentrate on her studies. Towards the end of the movie, when Miloni is traveling on a bus, a woman asks her whether she is the same girl who appears on the coaching billboard. After reflecting for a while, Miloni responds in the negative. She is not lying. She is no longer the person we see at the beginning of the film. Although her appearance remains unchanged, a lot has changed within her. She no longer identifies with the girl who was chasing the dream of being a chartered accountant. She was merely attempting to fulfil her parent’s ambition which was undermining her autonomy. Now, she has freed herself from the love-denying and life-denying aspirational pressure to be at ease with herself. She is no longer the same person.

We observe Miloni in the boat looking at the sea, away from the hurly-burly of life around her, intermittently closing her eyes in an attempt to extricate herself from the seemingly suffocating atmosphere. This could be interpreted as the beginning of her pursuit of silence. As a piece of soothing, non-diegetic music plays in the background, she isolates herself to be free from the family to roam around the Gateway of India where she is photographed by Rafi. This is the regenerative silence necessary to create a new persona for herself, one that is independent of the expectations of her parents or society. This is the silence that Max Picard refers to:

The silent substance is also the place where a man is re-created. It is true that the spirit is the cause of the recreation, but the re-creation cannot be realized without the silence, for man is unable wholly to free himself from all that is past unless he can place the silence between the past and the new.14

Photograph will be remembered for its subtle soundscape which highlights the communicative power of silence in human interaction. As philosopher, Mark C. Taylor posits “words allow silence to speak by unsaying itself”15. The plot of the film is centered around metropolitan life in Mumbai, a world full of continual distractions. The film’s most intriguing aspect is its attempts to construct silence amidst noise. Rafi and Miloni, the unassuming protagonists seem to be carrying an interior monologue throughout the film and cultivate silence as long as possible. Given the difference of age, religion, and class, a regenerative space is required where protagonists can reinvent themselves to engage with the other. Camera work also conspires with characters to conserve silence. However, the audience must be patiently attentive to capture these nuances and hear the echo of artfully articulated silence. This article deals exclusively with the restorative, comforting, and loving silence that pervades the selected film. Elsewhere, it would have been possible to explore malign examples of silence that can be repressive, traumatic, and hateful.