Introduction

With the early beginnings of a looming crisis in late 2019 in the city of Wuhan in China, the year 2020 was dawned with an unprecedented pandemic of which the scale, severity and implications were not known to many people in the world. While high levels of infections and spread of the virus – which was originally called Corona and later became to be known as COVID 19 – infected a total of 675,057,913 people and resulted an estimated 6,870,547 deaths throughout the world (John Hopkins University 2023). The years of 2020 and 2021 were under the strong grip of the virus while the life of people in many countries came to an almost standstill with restricted movements and interactions dictated by the newly imposed regimes called lockdowns and social distancing. The spaces of workplace, school and market were no longer allowed to be accessed physically but only or largely remotely by way of online interactions. While the different aspects of everyday life of people went through a process of radical transformation, a new lifestyle emerged gradually as a way of adaptation and resilience to the virus.

Thus, entertainment via online platforms and social media assumed a renewed pivotal role in this new lifestyle as a key coping strategy of recreation amidst the new forms of stress, anxiety and mental challenges that were spawned as byproducts of life under the virus. As such, films attracted large amounts of viewers, albeit online1, during this period while the regular cinema halls remained closed. A popular online platform film platform such as Netflix, for example, registered high traffic of viewership as the pandemic was spreading2. Largely, these online film platforms were streaming films that were already produced prior to the pandemic. At the same time, there was also a new trend of films being produced under restricted and difficult circumstances of the pandemic. This gave way to the emergence of a new genre of cinema variously called Covid Cinema or Pandemic Cinema based on a variety of productions of different scale and style from different parts of the world.

This paper documents the above experience in Sri Lanka during the period described above. The author uses his own personal experience as both film director and scholar as the main basis of the paper, to narrate the making of films during the pandemic. In a comparative approach, the author's experience is superimposed with other Sri Lankan film makers who used cinema as an artistic outlet to express themselves during the health crisis. The collective experience – author’s as well as those of the others – needs to be understood within the framework of a socio, political and economic crisis which also struck Sri Lanka shortly after the pandemic. In fact, in Sri Lanka, the pandemic coincided with a period during which the country was undergoing a key political transition which was not smooth (Fernando: 2023). Therefore, this paper strives to bring in the layers of individual (author), collective (film makers in Sri Lanka) perspective and to understand how these cumulative efforts were informed or influenced by the broader context and macro dynamics of the country and perhaps beyond.

The temporal range of the inquiry spans from January 2019 to December 2022. The year 2019 is included as it paved the way for many changes that took place in the political sphere from 2020 onwards. The year 2019 is also used to examine the film scene in the pre-Covid period that could enable a comparative analysis with the Covid period. This paper is presented in the following sequence so that the three levels of inquiry can initially be delineated and be cross referenced in the subsequent discussion to understand the interplay between the different levels. First, a broader context of Sri Lanka pertaining to the pandemic period and the year preceding the pandemic is presented followed by a general overview of the mainstream cinema during the pandemic period with an emphasis on how the film industry was affected by the disruptions. Thereafter, a general overview of the mainstream cinema during the pandemic period with an emphasis on how the film industry was affected by the disruptions. Then a recollection of cinematic outputs during the years of 2020 and 2021 that can be discerned as Covid Cinema or Pandemic Cinema are presented. Thereafter, the author’s personal narrative is unfolded to elaborate the specific personal, social, and political circumstances under which his films were made during the early stages and height of the pandemic. Finally, general conclusions are drawn with patterns of interactivity between the context, collective and the personal spheres.

Sri Lankan context in before and during the pandemic

This section gives an overview of the broader political context that prevailed in the country a year before the pandemic as well as a contextual narrative as the pandemic unraveled. The reason for bringing in an analysis of a pre-pandemic period is because there was a political spillover from the preceding that shaped the character of the political conditions that prevailed during the time when the pandemic made its way to Sri Lanka3. The temporal parameters of this analysis span from early 2019 to the end of 2021.

Run up to the pandemic period

The year preceding the pandemic in Sri Lanka was as unprecedented and chaotic as the pandemic itself but at a political level. Out of the blue, in October 2018, the then President Sirisena sacked the sitting Prime Minister and appointed the leader of the opposition as the new Prime Minister. This led to a crisis as this abrupt act was contested with two claimants. Dubbed as a constitutional coup, the previous PM refused to leave the official residence, while the newly appointed PM selected a new cabinet of ministers and assumed duties. Parliamentary proceedings were disrupted and sabotaged while mayhem reigned. Finally, it was towards the end of the year after a series of hearings at the Supreme Court that the President’s act was declared unconstitutional and the status quo prior to his action was restored.

Not so late after the above political roller coaster another calamity occurred which also had an impact on the cinema industry. In April 2019, on Easter Sunday, a series of multiple bomb explosions took place in several prominent locations –including Churches and leading tourist hotels– in the city and its outskirts, killing an estimated 296 people and injuring thousands. This came as a shock because such occurrences were rare since the end of the war in 2009. As there were claims that those responsible for the explosions –carried out in suicide attack style– came from a radical Muslim group. As such, the Easter Day bomb explosions unleashed a wave of anti-Muslim sentiments as well as some riots and violence against the Muslim people, particularly in some areas where their dwellings or business places are concentrated. At a political level, the Easter Bomb explosions were highlighted because of a serious security lapse and the main oppositional political force that was in power from 2005-2015 exploited this situation to undermine the incumbent government. It is in this context that the same oppositional force promoted a new leadership –as its candidate for the presidential elections to be held in November 2019– who can regain national security and stability.

Gotabhaya Rajapaksa (hereinafter referred to as GR), a lieutenant colonel of the Sri Lankan Army from 1972-1992, and Secretary of the Ministry of Defense from 2005-2014, secured a comfortable victory in the presidential election. GR had the advantage of being the brother of Mahinda Rajapaksa, who served as president from 2005 to 2014. GR’s victory at that stage of history was considered politically significant as his victory was not dependent on the so-called minority votes of the Muslim and Tamil constituencies. It was claimed that this was the first time a president has been elected solely based on the overwhelming Sinhala-Buddhist support. GR’s campaign was firmly grounded in Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism, capitalized on the backlash to the Easter Sunday bombings. Generally, the Rajapaksa brothers are known to be taking a firm and tough position on security issues, having ended the nation’s long civil war in 2009 and were thus seen to offer strong leadership to quell extremist violence.

With the victory of GR in November 2019, the then prime minister and cabinet resigned, paving the way for GR to appoint his loyalists. However, he lacked a working majority in Parliament. President GR and his loyalists openly expressed displeasure at Constitutional restrictions on executive powers they saw as obstacles to fulfilling his election promises. The 19th Amendment trimmed executive powers and established independent commissions, such as the Election Commission and Police Commission, to check the president’s power. Gaining a two-thirds parliamentary majority for the president’s party was deemed essential to undo the restrictive revisions to the Constitution. Hence, there was an urgency to holding general elections to ride the wave of President GR’s November 2019 victory. It was at this time with the advent of major socio-political change that the new coronavirus made its first appearance towards the end of January 2020.

COVID 19 enters Sri Lanka

The first confirmed case of coronavirus was reported in Sri Lanka on 27 January. The patient was a Chinese tourist from Hubei Province. One week later, 10 March, the first local case was reported: a tourist guide who had led a group of Italian tourists. The Chinese tourist was immediately admitted to a local hospital, underwent treatment, and was discharged on 19 February. Both the Chinese woman and the tourist guide were treated at the so-called “IDH,” or Infectious Disease Hospital, which later came to be known as the National Institute of Infectious Diseases. It is considered a high-service level hospital focused on infection control, HIV, and other infectious diseases. Quarantine centers were also set up by the Army in their facilities in Diyatalawa, Punani and Kandakadu. Later, many other quarantine centers were opened by the military. Private hotels were also allowed to offer quarantine facilities for a considerable tariff. However, the government’s attention was soon distracted from the pandemic to politics as the president dissolved the Parliament on 2 March, calling for snap elections six months early. The elections were to be held on 25 April. But the spread was escalating, and pressure was mounting on the government to take charge of the pandemic. As a result, the main airport was closed on 18th March indefinitely while the government imposed a 52-day curfew (Sri Lanka’s modality of lockdown) between 20 March and 10 May.

The lockdown created mayhem and disruption to the daily routines of people as the places of work could not be accessed and as shops, markets and schools were closed. There was public unrest and protests that led to strict imposition of curfew and those who violated the curfew rules were arrested and kept in quarantine centers forcibly. Due to mounting pressure, the election that was planned for 25 April 2020 was postponed indefinitely. However, there was another form of pressure from the political authorities to hold the elections before 2 June because the dissolved Parliament needed to reconvene by then in accordance with Constitutional requirements. The Election Commission wrote to the president to inform him that due to COVID-19, they could not organize an election before 2 June. Finally, after a long tug of war, the elections were held on 5 August 2020.

Unrest, repression, militarization, and freedom of expression

One of the initial forms of unrest occurred with riots in a prison which had 26,000 inmates and it was meant to accommodate 10,000 and thus posing an imminent threat of the virus spreading fast due to inadequate social distancing. Two prisoners were shot dead during the prison riots. These deaths preceded the COVID deaths. There was also another form of controversy over the banning of burial of the corpses of the Muslims who died of COVID-19. This created a wave of ethnic tensions. The unrest and frustration of the people were expressed widely in social media. Often, the president, the government, the police and the military were heavily criticized over their heavy-handed approach during the pandemic. For a certain period, the government imposed social media blackouts and in some instances those who made critical posts on social media were arrested or threatened to be arrested.

The military played a key role in Sri Lanka’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak. The Army commander was heading the National Operations Centre on Prevention of COVID-19 and the military was tasked with carrying out search operations for contact tracing and arrests. The quarantine centers were run by the military, often using their camps, infrastructure, and personnel. Moreover, the ministers of health and agriculture were replaced by two military officers on the very first day the country began to reopen after the 52-day curfew. The military was also disproportionately represented on the Presidential Task Force in charge of economic revival and poverty eradication, a mechanism set up to respond to socio-economic challenges created by the pandemic.

Concluding remarks

COVID-19 hit Sri Lanka at a politically turbulent time when a new president was just settling into his role and preparing to further consolidate executive power. The curfew provided an opportunity for a president who came from a military background and favored the military over existing administrative structures to establish an authoritarian style of governance. At a time when the Parliament had been dissolved and the court system was not fully functioning, the president was able to use and expand executive powers to marginalize legislative and judicial checks-and-balances to further his agenda. In Sri Lanka, from 3 January 2020 to 26 April 2023, there have been 672,139 confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 16,839 deaths (World Health Organisation 2023). While the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in Sri Lanka may seem relatively limited compared to other nations it has been exploited politically to consolidate authoritarian governance. Fortunately, the public health consequences were limited owing to a free healthcare system and an efficient public health network. However, the challenges that this period posed on democracy, the rule of law, and constitutional freedoms of citizens remained as dangerous as the COVID-19 virus.

Sri Lankan Cinema during the pandemic

This section gives a detailed account of the films that were released in cinema halls in Sri Lanka in 2020 and 2021 and the period that coincided with the onset and escalation of the pandemic. The account also includes the spells of closures of cinema halls as preventive measures taken by health authorities to contain the spread of the virus. The section starts with a general overview of the film industry that prevailed around the time when the pandemic started.

Sri Lankan Film industry in the immediate years prior to the pandemic

The Sri Lankan film industry has been struggling for many years due to a variety of reasons, the main reason being the dwindling number of film-goers. Since the 1980s, many people have preferred a convenient and inexpensive way of watching the so-called ‘tele-dramas’, serials, on television. The other factor that further hindered people from watching films was the onset of a civil war, mainly in the North and East and an insurrection in the rest of the country in the late 80s. The war remained for three decades and impacted daily life. The film screening was not practical, particularly the evening and night screenings. 1983, the precursor to the war, broke out in the form of ethnic riots, and a substantial number of film halls as well as studios owned by Tamils were burnt. Most of these halls have not been restored since then. As a result, running cinema halls has not been financially viable and many halls have been closed or handed over for other businesses. This in turn posed serious challenges to film production to make it financially viable. It is only a few films that qualified as commercially successful while many incurred heavy losses. Despite these serious limitations, 26, 28 and 29 films that are locally produced have been released in the years 2017, 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Films released in 2020

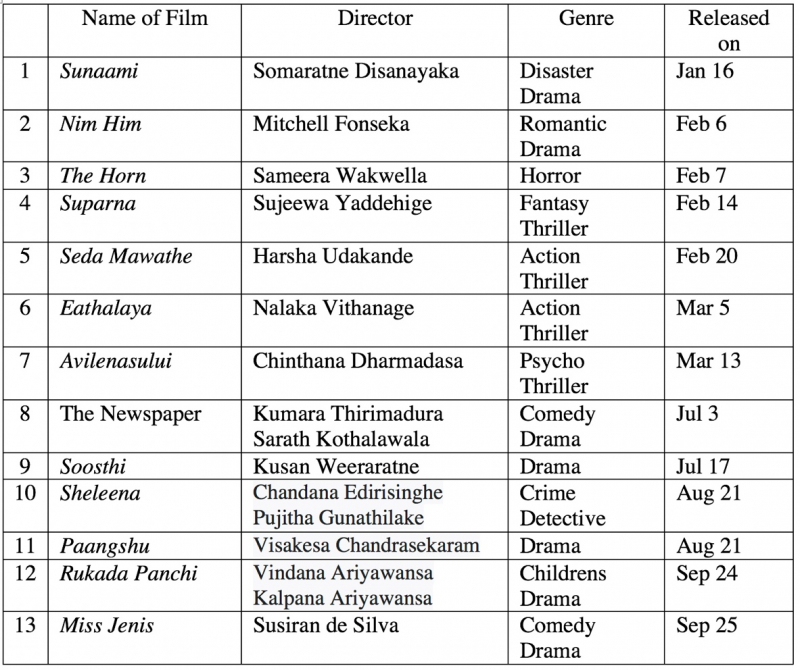

The year 2020 began with the release of a film called Sunaami (Tsunami) which was directed by Somrathna Disanayaka whose previous film Sooriya Arana (released in 2004) recorded the fourth highest box office income of SL Rs 120 Million. Though Sunaami was not able to reach that degree of success, the director’s reputation as well as the nature of the plot enabled the film to make a reasonable revenue. The first six films listed in the following table were released before the onset of the pandemic. The seventh film on the film, Avelena Sului (Inflammable) (released in 2020) by Chinthana Dharmadasa was released on the 13th of March but from the very second day of the film, the film halls in the entire island were closed as a COVID-19 preventive measure. The closure of halls continued till the end of June. As can be seen in the table, it is only in July that two films were released after the closure of halls for about three months. The second spell of closure was imposed from early October when the second wave of the pandemic occurred with the so-called Minuwangoda Clusters originated from some workers in a garment factory.

Table 1: Film Release 2020

Source: compiled by the author, based on various issues of Sarasaviya, the film newspaper

Films released in 2021

After a period of three months of closure of film halls due to the second wave of the pandemic in Sri Lanka, the halls were reopened under strict guidelines from 1 January 2021. To maintain social distance, the halls were instructed to leave every other seat unoccupied. Practically, this halved the capacity of the audience that entered the hall. Interestingly, the first film to be released in January 2021 (see Table 2) was one that had a plot that unfolds against the backdrop of the early stages of the pandemic under a situation of lockdown.

Aale Corona

The film was shot in a realistic style. The film was claimed to have been completed in 17 days during the long COVID-19 epidemic season. The film depicts a couple living alone during the COVID-19 period and a 42-days of a lockdown period. It also emphasizes experiences that led to the battle of life in the face of social and economic crisis. About 90% of the film's frames are shot in the same room where the young couple was compelled to lock themselves in.

(Sinhala film, Family Drama, 58 mts, Director: Sanjaya Nirmal)

Aale Corona (Love in Corona) (released in 2021) was shot in late 2020, within a span of four days, with a low-budget and was shown in 25 cinema halls for about a week and this was expected by the producers who had an alternative strategy of streaming the film in an online platform owned by them4. The online streaming was watched by a substantive number of viewers who were subscribers to the platform concerned and the film was also included in the inflight entertainment list of the national carrier, Sri Lankan Airlines that further widened the outreach of the film5.

From January to April 2021, a few more films were released but the turnout of the audience was limited. With the onset of the third wave of the pandemic in Sri Lanka, the film halls were closed again until further notice. In July 2021, the Cinematographers’ Association announced that the closed cinemas would reopen from July 16, 2021. Following a discussion with President Gotabhaya Rajapaksa on July 8, 2021, approval was given to reopen cinemas. However, from May to October 2022, as can be seen from the table below, no films were released. It is remarkable to observe that six films were released within a span of two months in November and December 2021.

Table 2: Films released in 2021

*A Tamil Language film. The only Tamil language feature film released in 2020 and 2021

Source: compiled by the author, based on various issues of Sarasaviya, the film newspaper

Films made during the years of 2020 and 2021

While film screening was seriously restricted due to the closure of film halls, the necessity to maintain social distancing and people’s fear to visit cinema halls, a couple of film productions were launched during the Covid period. Veteran filmmaker Asoka Handagama was to launch the filming of his new venture, Alborada (released in February 2022) in 2020. The film was based on the period of stay of the celebrated Chilean poet Pablo Neruda as a diplomat in the colonial Ceylon. The production entailed a cast of European actors who were to travel from overseas. The production took place in between two lockdowns, from June to August. The actors were expected to serve quarantine terms on their arrival6. Prasanna Jayakody, another renowned director, scripted a film which was tentatively named, Korona kaalee aalee (love in the times of Corona) (released in January 2021) and carried out part of shooting in between the lockdowns. However, the remainder of the filming was halted as the director realized the reality of the pandemic at the very early stages he used as the basis of conceptualizing the script changed drastically after a few months. The film was abandoned as a result7.

Eranga Senaratne’s film Mona Lisa (released in February 2022) was shot during two lockdowns in 2021, during the months of June and July. The production was carried out under dire circumstances including difficulties of finding places to buy food for the crew and cast because many eateries and hotels were closed during that time8. The director’s experience during the above production, as well as the fact that the area where the shoot was carried out was cordoned off for an extended period of quarantine soon after the film, inspired him to write a script of a film that captured the realities of the pandemic. The plot was around a female colleague who visits her boss when she hears that he is ill and while she was in his house, the Public Health Inspector appears to announce that the man is found COVID positive (as per a test carried out before) and the inmates, the boss, and the visiting colleague, are compelled to be indoors for 21 days under quarantine rules. The film, titled Taj Mahal (to be released), was shot in October 2022 and a preview of the film was organized in early 2023, awaiting its release in 20239. The filming of Udayakantha Warnasuriya’s Ginimal Pokuru (released in December 2021) started in April 2021 but was postponed till August 2021 due to lockdowns and COVID-19 restrictions of inter-District travel and banning of gatherings and group activities10. However, the postproduction was carried out efficiently so that the film could be released on 3 December 2021. Sanjeewa Pushpakumara’s film Vihanga Premaya (Peacock Lament) (to be released) was shot in 2020 with many stages of disruptions due to pandemic restrictions and lockdowns. The last stages of shooting of another film by him, Aasu (to be released), took place in early 2020 and was disrupted as the location of the shoot was a leading hospital in Colombo where a COVID-19 patient was found in the early stages of the pandemic11.The two films are yet to be released (as of May 2023).

Veteran filmmaker Prasanna Vithanage, had just completed his latest film then, called Gaadi (released in January 2023), during the initial outbreak of the pandemic. In an interview, he says that he was in Europe at this time with his film to be screened in a row of film festivals but failed to do so as the festivals got postponed12. Since Gaadi has not yet been released in Sri Lanka, the director had refused to present it at the online-festivals due to possible threats of piracy. Gaadi was released only in early 2023. The Caméra d'Or winner in 2005 at Cannes, Vimukthi Jaysaundara, scripted a film around a COVID theme and the film was to be produced by Priyantha Ratnayaka of Teleview. The film was to be shot in the Riverstone area where a quarantine center was to be made as the set. After several visits to the location, the production was abandoned in mid-2020 when conditions were not conducive for an operation such as a film production that involves many people working closely for an extended period of time13. Another senior cinema and television director, Sudath Mahadivulwewa claimed that the pandemic period was the most productive period of his life as he was able to complete three film scripts while being stuck at home for long periods14.

Concluding remarks

The mainstream feature films during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 did not make a significant impact among the Sri Lankan audience as the viewership was very limited and screenings were disrupted by the closure of halls for many months coinciding with three waves of the pandemic that was experienced in Sri Lanka. As mentioned in the introduction, the usage of online and social media platforms was very high during the pandemic period as people were compelled to stay indoors. Sri Lanka was no exception to this trend experienced globally. Production and postproduction work of a few films were carried out in 2020 and 2021 under difficult circumstances and during the short windows between lockdowns. However, the production of mainstream feature films as outlined in the last subsection, remained at a satisfactory level in spite of the trying circumstances dictated by the pandemic. This shows a sense of dedication and resilience on the part of the Sri Lankan directors. Their ability to improvise and adapt to new conditions is very apparent in these efforts. The interviews suggested that many of the directors opted to work on low-budget films with small crews as funding was limited and there were restrictions on the number of people to gather in locations where shooting took place.

Emergence of a Sri Lankan Covid Cinema

Breaking ice – the first Covid cinematic expression

In a context where the usage of online and social media platforms became high as people were stuck to the confines of households due to pandemic measures, one of the leading Sri Lankan film directors, Asoka Handagama, launched an exploratory and experimental cinematic venture in the very early stages of the first wave of the pandemic in Sri Lanka. Handagama used the Zoom application to capture the shots of the characters of his script. The actors were dispersed in different locations – as travel and social gatherings were not possible during the lockdown period – and they were captured by Zoom’s online camera and sounds. Handagama’s film was titled Alkohol nethi biyar (Beer without alcohol) (released – online – in May 2020).

“Beer without alcohol” is based on a zoom call between four friends (played by Nadie Kammallaweera, Samanalee Fonseka, Indrachapa Liyanage and Rukmal Niroshan) who have been confined to their respective houses due to the pandemic travel restrictions and lockdowns. The entire story gravitates on a “gone girl” (Shashini Gamage) –who left her husband (Rukmal Niroshan) just before the day of curfew and while her husband reveals his “less-dramatic” mediocre life, where he found his wife on a chat room, and they got married without any conflicts like everything else in his average life. However, the sudden disappearance of the wife was due to a rumour about the husband’s true moment of “falling in love” with another woman and the Zoom conversation is continuing with his other friends who tend to reveal their “true” moments of “falling in love” in life. In the movie a specific question is repeatedly asked by the character played by Nadie Kammallaweera; “Did you fall in love?”, opening an avenue for its viewers to dive deep into what it meant by “falling in love”? (Kodagoda 2020)

(Sinhala, drama, 54 mts, Directed by Asoka Handagama)

This film was premiered online on 10 May 2020 on Youtube platform and could be accessed online freely thereafter15. Given the novelty of the production concept, Handagama’s reputation as a filmmaker and the lacunae in cinematic entertainment with a local production during the pandemic, made Beer without Alcohol popular among the public that follows alternative cinema. The film attracted a great deal of online discussion events as well as film reviews (for an example: Raghavan 2020). Though it was not produced in a conventional cinema format and distribution, Handagama’s film set a novel trend in Sri Lanka, perhaps globally as well, ushering in a genre which can be called the Pandemic Cinema.

A momentum builds

Derana, a private Sri Lankan TV channel, produced a pandemic-related teledrama series with five episodes under the theme “Lock Down Stories” that went on air in the month of June 2020. This series was shot in three locations, in and around Colombo, where the inhabitants were under lock-down and was later edited around a common narrative of how the pandemic affected the daily life of a middle-aged couple, a young couple and a group of lodgers sharing a rented house. The coordinating Director was Namal Jayasinghe while Jagath Manuwarna, Nalin Lucena and Nilanka Dahanayaka functioned as directors of the three locations16. However, the format was not strictly cinema, and the distribution was carried out as telecast.

An attempt to revamp conventional film projections

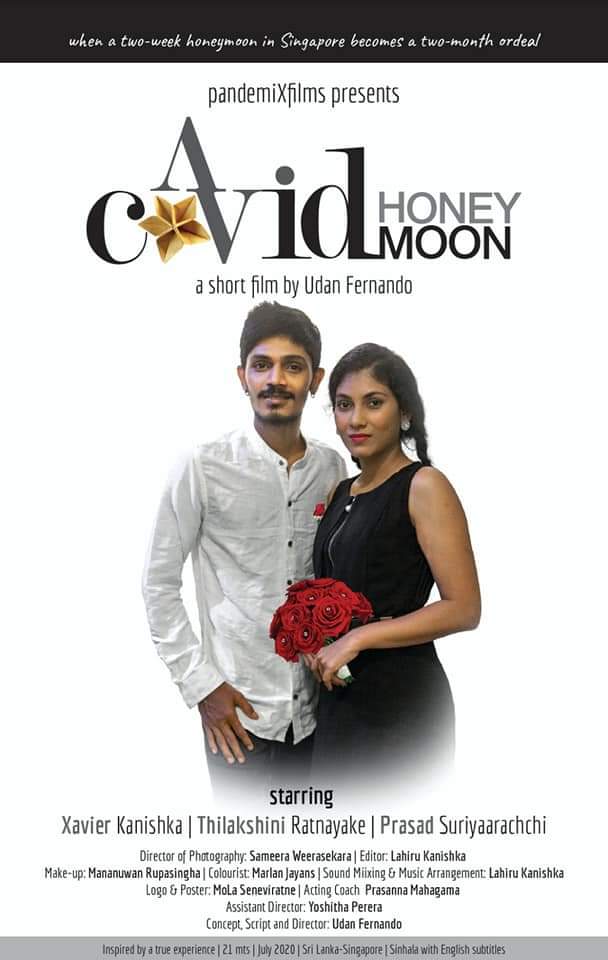

Perhaps for the first time a screening of pandemic-triggered films with a conventional projection modality in a physical space with an in-person audience since the onset of the pandemic took place, when Goethe Institute’s Film Forum curated a short feature film titled A Covid Honeymoon (released in July 2022) and a few mini-shorts directed by Udan Fernando (the author of this paper) from 28-30 July 2020 (The Sunday Times 2020). This was the first time the Goethe Institute organized an event for people to take part in person since the pandemic broke out. The screening was organized under a strict social distancing seating arrangement that necessitated extra screenings because of the lessening of the seating capacity due to social distancing.

The Jaffna Film Festival 2020 was held on 29-31 January 2021. Among the short films that were selected for the festival, there were two short films produced in Sri Lanka that were made around a pandemic plot: My father is a Dog (released in January 2021) and A Covid Honeymoon. There was a reference to the second film above. The synopsis of the second film is given below:

My Father is a Dog

The Film is providing the audience with a unique cinematic experience, the pose of technical excellence and strong performances and for allowing them to interpret the dynamics of the relationship between the father and his daughter who are under quarantine, thereby taking on issues that extend beyond the quarantine period.

(Drama, Sinhala, 10’39”, Director: Tharindu Lokuarachchi)

An anthology of pandemic films

There was institutional process of pandemic cinema production initiated by Agenda 1417 with the support of the International Relief Fund of the German Federal Foreign Office, Goethe-Institut and other partners, that brought together a group of young men and women who created nine films, featuring different perspectives of the COVID-19 pandemic. Themes varied from love, relationships, feminism, child rights, the plight of artistes during the pandemic, addictions, religious beliefs and the rights of the LGBT groups.

Shot from end September 2020, the project was executed using a single mobile phone to capture the images and one sound recordist, shared by all the directors for each film. It was shot under available lighting conditions with a director, camera person and sound recordist as crew and with mostly non-actors enacting the scenes. A few professional actors also took part in creating some chapters of the anthology film. The entire pre-production including selecting locations, background settings and costume selections were done via online.

The Sri Lankan anthology titled Goodnight Colombo! (released – online – in July 2021) comprised nine short films; 'An Emergency' by Nipunika Fernando, 'The Washroom' by Krishan Kodithuwakku’, ‘The Delivery' by Lanka Bandaranayake, 'An Overdose' by Muvindu Binoy, 'A Wounded Artist' by Sumudu Athukorala, 'The Pet' by Fathima Shanaz, The Telephone Call' by Danushka Wijesooriya, 'An Avoidable Contact' by Yoshitha Perera, 'A Working Girl' by Rahul Ratnayake. These films were in Sinhala. Two short films in Tamil on pandemic-related plots; Another Lesson by Dimon John and A Marriage Proposal by Mathavan Maheswaran were produced as part of the same process under the supervision of Agenda 14. The film anthology was released online on 7 July 2021 for 24 hours (Fernando 2021).

Other productions on the pandemic and under pandemic conditions

As They Speak (Sinhala/Tamil, with English subtitles, documentary, 51 mts, Director: Anomaa Rajakaruna) (released in Feb 2023) documented the experience of twelve women -- from different walks of life – with the pandemic in their daily routines of life. The shooting of the film was carried out in late 2021, during some period of the lockdowns. However, the documentary was released only in early 2023. An economic crisis was looming gradually towards the end of 2021. One of the early signs of this crisis was the fuel shortage. This limited the ability to use private transportation. The common mode was public transport. Another film initiative with the university students during this period has been affected by the fuel crisis. The film crews had to carry cameras and other equipment in backpacks and had to use public transportation. Public Health Inspector’s permission had to be obtained for each shoot. In addition to usage of face masks and sanitizer, social distancing had to be maintained in the film location. During the time when travel from one district to another was banned, the shoots were carried out in different districts with different actors and the images were subsequently merged with VFX technology18.

Concluding remarks

As remarked by the veteran filmmaker, Prasanna Vithanage, the COVID period was the “darkest winter for the mainstream cinema”, the pandemic period also created a sense of renewed interest on films, particularly by the younger generation:

There are many positive signs that have appeared during this lockdown period. There had been a huge interest in cinema and also in local cinema. This is especially among the younger generation. They have watched many old films via digital media through their phones and laptops. There are also several local digital platforms (Fernando, S 2020).

As the foregoing section shows, there had been a mixture of individual and institutional initiatives to make short films and documentaries during the pandemic years in 2020, 2021 and beyond. The spirit, dedication, and commitment of these predominantly young film makers, with a fair representation of female filmmakers, were very high. This is something remarkable at a time when the pandemic dampened the overall morale and spirit of many people. The systematic institutional approach adopted by Agenda 14 in promoting young filmmakers during this challenging period is commendable. Agenda 14 has not given up holding their regular film festivals – Agenda 14 Film Festival and Jaffna International Film Festival – in spite of trying circumstances under the pandemic. The role of Agenda 14 during the pandemic is important for another reason from an institutional perspective. The work of one of the leading film schools run by Sri Lanka under the Sri Lanka Foundation Institute and Sri Lanka Television Training Institute (SLTTI) was badly affected by the pandemic restrictions as the students could not travel due to restrictions and lockdowns19.

Film making as Covid coping? A personal narrative

This section presents the author’s own experience in engaging in a cinematic venture in the midst of the early stages of the spread of the virus. The section describes the general circumstances of his professional and personal life during that period as well as his intimate experience of being quarantined under trying circumstances. The process of conceptualizing the film, scripting, production planning, production and the screening is then outlined. Here onwards, the text uses the first-person tense that suits well to narrate the personal experience.

Transitions in life

I was to start the year 2020 with great expectations and hopes as I made plans to change from a full-time job in Sri Lanka to an independent consultant to function from Singapore, with a goal of scouting for jobs of research and consultancy in Southeast Asia, particularly in Cambodia and Myanmar. I made good progress in making inroads to these two countries. I was to visit Myanmar in May 2020. I was able to secure an assignment there from September to November 2020. I visited Cambodia in early March 2020 for an exploratory visit. I was making good progress with my meetings in Phnom Penh. I then moved to Battambang for another spell of work before I was to finally reach Siem Reap for a crucial meeting with a potential client. The COVID-19 spread was raising its head by this time but it was not that pervasive. People in Cambodia were practicing precautionary measures such as lessening or avoiding physical contact, the use of sanitizer and masks but the situation has not yet reached a serious stage.

The pandemic heightens

While I was in Battambang, the Singaporean government gave 48 hours to its citizens and residents to return to the country as the pandemic levels have reached a serious level. I had to rush to Siem Reap to catch a flight and reach Singapore, only a few hours before the deadline. My original plan was to leave for Colombo for a week and then travel to the UK for a work-related visit. Meantime, the Colombo airport was closed indefinitely, I was compelled to stay on in Singapore which introduced what was called a ‘Circuit-Breaker’, the Singaporean version of lockdown, that restricted peoples’ movements except for essential visits to buy food, medicine and engaging in exercises. Similar practices, with different variations, were called Lockdowns in other countries.

The new home-bound life with the fear of contracting the virus with a gradual shift to working online became the new norm. I too went through the ups and downs of this new norm with which many individuals and families were struggling. I had my share of anxiety, uncertainty, and tensions while the long period of stays at home sans a busy lifestyle offered an opportunity to reflect and think too. Though the airports were opened after a few weeks, the flights were limited. This was particularly the case with flights to Colombo. Seldom, the so-called repatriation flights were in operation. They were only available once a month and with long waiting lists of passengers who were desperate to get back. In Singapore, where I was based, there were many such cases of tourists who were stranded, students whose courses were called off and others who lost their jobs due to the pandemic.

Quarantine in a military facility

After a long wait of about two and a half months, I was able to secure a reservation in a repatriation flight that was to leave from Singapore to Colombo on 2 June 2020. On the eve of my departure, I came across a news story about a young Sri Lankan couple who had come to Singapore for their honeymoon, with only very little money which evaporated fast given the high cost of living in Singapore. But they could not leave Singapore as there were no flights and at the same time, they had no means to stay on. This dramatic story deeply affected me and clouded my mind as I was waiting for my flight the next morning. I could not believe that the same couple was with me on the flight to Colombo, the next day.

After a stressful flight to Colombo and a few hours of going through special procedure in the airport, including PCR Tests, the passengers were huddled upon to a bus that was to reach a quarantine center run by the military located in a remote area called Punani, in the Eastern part of the island, which was about 250 kms away. The so-called ‘Singapore batch’ included about 250 persons. We were expected to have accommodation in shared dormitories for a period of 14 days of quarantine. The facilities at the center were at a bare minimum level given the vast numbers of people who were to be quarantined. Baths and toilets were to be shared by many people. This created a sense of fear and anxiety about the imminent risk we would run if one is found positive for the virus.

Quarantine dormitory becomes a film lab

The dormitory was noisy. Amidst the constant chatter of the fellow quarantine-mates in our dormitory, with many upheavals at the quarantine centre and the grim circumstances facing us all, I sought refuge in a corner bed that became my working, thinking and dining space. To distract myself from being anxious in a very negative environment, I tried to concentrate on something that occupied my mind. It is at this corner bed that I started writing a script based on the story that I heard before my departure. The story completely occupied my mind and aroused my imagination so that I could improvise the storyline that is cinematic for a short feature film. Since I was in a ‘cinematic’ mode, a few other mini-short-films were also conceived based on the daily routines as well as dramatic events at the quarantine center. I found a young undergrad student who was using a computer that had decent editing software. Though this young student had not used the editing software, he was adventurous and bold enough to do the editing of the still photographs and video footage I captured in the quarantine center. Thanks to this quarantine film collaboration, I was able to create the following mini-shorts during my quarantine term from 3 – 16 June 2020:

Gastro Quarantino

A montage of 42 meals served over a period of a –two-week Quarantine Term in a Government Quarantine appreciating an unrecognized group of ‘frontline workers’ vis a vis the reality of private quarantine facilities offered by star hotels at exorbitant prices and the high moral ground they maintain their offer as a national service.

(Documentary, 1 min, 05 Sec, English)

The Man-Eating Cobra in Punani: A Rediscovery of Quarantine Jungles in Modern Lanka

An insignificant and small hamlet in a remote and cut-off area in Eastern Sri Lanka comes to the fore with the current Covid-19 pandemic while refreshing a bad old memory in the past, exactly 100 years back during the colonial period, where the same village was terrorized by a man-eating leopard that took the lives of a few villagers in Punani.

(Documentary, 5 Min, English – with a narration, with English Subtitles)

A Special Announcement

The only form of communication from outside world for those who are serving a term of quarantine in an isolated, enclosed and limited area is the twice a day visit by the person who checks temperature and an occasional announcement from a badly maintained public address system that uses a pair of old styled loud speakers that transmits messages that sometimes hit the heart more than the ears given the content of the message to people who are in a constant state of fear and anxiety.

(Documentary, 1 Min, 05 Secs, English, with English Subtitles)

Going Home

The date of departure upon completion of a term of two-weeks’ quarantine is often not certain. It is sometimes like a moving target. If one of the fellow members from the same batch is found positive then the entire batch gets an extension of a week or sometimes two. The majority of those who are quarantined in centers are the returnees from overseas who have not seen their families and loved ones for a long period of time. With the greatest difficulty, they get themselves on a special repatriation flight to Sri Lanka. Upon arrival, they are expected to go straight from the airport to a quarantine center for two weeks and that period gets extended sometime, leaving them with a sense of uncertainty as to when they could reunite with their families and loved ones.

(Documentary, 2 Min, 45 Sec – English, with English Subtitles)

The script of the main story progressed well with some ups and downs in the general environment such as a fear of someone contracting the virus and then the entire group being taken for PCR test and the uncertainty and fear that existed until the report came. I was able to get in touch with a prominent film maker, Asoka Handagama and an experienced documentary director and photographer Sharni Jayawardena, to seek feedback to further improve the script. While many drafts of the scripts were being churned out, I was also keen to do the casting and production planning. As for photography, sound, and editing, I had my own crew who worked with me on a documentary film I directed in 2019. While I chose to take that entire crew onboard for this production, I was contacting a few actors and had some kind of online auditions and negotiations before I finally chose the three-member cast. Meantime, I was writing to about 15 people and agencies to seek funding and the response was negative. Finally, a friend of mine came forward to be the producer on the basis that he goes anonymous.

By the time I left the quarantine center, I had a finalized script, a production plan and an agreement with a cast and crew. However, upon returning home, the procedure then was to report at the Police Station and then register under the Public Health Instructor of the area who will arrange another two weeks of quarantine at home. I made use of this time to make the set of the shoot in a large bare space in a new floor of my house which has been completed. Suppliers and friends left different items – sofas, carpets, TVs, chairs, etc. – at my doorstep, as I expected to be isolated during the second stage of quarantine. Upon completion of that period, we were able to do the production as well as the post-production without any delay. The film was dubbed “A Covid Honeymoon” and the following is the synopsis of the film:

A Corvid Honeymoon

With their hard-saved $1,000, a young Sri Lankan couple fly to Singapore for a two-week honeymoon, with little or no idea about Covid19. The outbreak spikes during their honeymoon and a lockdown gets imposed. The two-week honeymoon becomes a two-month ordeal with no flights to return and nowhere to stay and with only $ 20 left in hand.

(Short feature, 21 Min, Sinhala with English sub-titles, July 2020)

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AUaY2CnVTFY

This film as well the mini shorts that were produced were premiered at a film screening at the Goethe Institute, in Colombo under its Goethe Film Forum, on 28-30 July 2020 (The Sunday Times 2020). The film was also selected to be screened at the Agenda 14 Film Festival held in Colombo and Jaffna Film Festival in the latter part of 2020. The film received satisfactory coverage from national newspapers. Several reviews were carried out in Sinhala as well as English in national level newspapers and online publications (for example, Boange 2022, Jayssinghe 2020).

Concluding remarks

Though I followed a course on cinematography way back in 1984/85 and a refresher course on anthropological film making in 2007, a film directed by me came only in October 2019. It was a 52 minutes long documentary about two former rebels. As such, by the time I ventured into making A Covid Honeymoon in June 2020, I was not an experienced film maker. Also, I have not laid my hands on the category of feature films. In hindsight, I tend to think that the dire circumstances that I was going through during the pandemic and the stressful stay in a quarantine center in a remote area run by the military with very minimalistic facilities threw me to a desperate act of refuge and a means of coping which was the conceptualization of the film, A Covid Honeymoon and the production of a few other mini-shorts during the quarantine period. The story I heard on the very eve of my departure to Sri Lanka was a very compelling one that hit me like a virus and made me preoccupied entirely during the long hours in the airport, flight and a long overland bus-trip from airport to the quarantine center. I also feel there was an element of empathy and relatedness on my side with the original story I heard and the one I improvised as the script of the film. Hence, I could conclude that it was a film born out of a situation of overlapping crises during the early stages of the pandemic which was dramatic given the newness of the pandemic and the imminent threat of dying as many deaths occurred during this phase.

Overall discussion: the interplay of the macro, collective and personal

Clearly, the mainstream feature film industry in Sri Lanka was badly affected by the pandemic. The closure of cinema halls due to health measures, introducing social distancing in film halls (thus halving the seating capacity) and people’s fear of going to cinema halls, seriously restricted the viewership and thus the revenue of cinema halls in turn might have made the producers incur losses. Hence the impact was on different levels of the film industry. There was only one long feature film that captured a pandemic theme (Aale Corona) while another was conceived and half-shot (by Prasanna Jayakody) but was abandoned halfway. Another film was produced in 2022 on a pandemic theme (Taj Mahal) but has not been released (as per May 2023). Therefore, as far as the mainstream film industry was concerned, the emergence of a trend that can be called COVID-Cinema or Pandemic Cinema was limited, insignificant and unnoticeable.

However, there was a considerable trend of making short films with a variety of plots around different aspects of the pandemic. Given the scale and vibrancy (the lack thereof) of the film industry in Sri Lanka, the number as well as the quality of short films that were produced during the pandemic is impressive. Clearly, one can discern a body of films produced in Sri Lanka during the pandemic period and around the issues of the pandemic that fall under what emerged as a new category either called Covid Cinema or Pandemic Cinema.

The themes and plots of these short films revolve around tensions in relationships, disruptions and complications of family life and livelihoods caused by the necessity to stay indoors due to lockdowns and immobility due to travel restrictions. The films could fall under a genre of drama with a heavy focus on human relations within structures of love, romance and marriage. Therefore, largely, the plots as well as the corresponding shots/locations were restricted to domestic spaces. In a way, this is understandable as the pandemic restricted life to domestic spaces. The strangeness of all members of a household staying together all the time for long periods caused tensions within families and couples. Hence, relational dynamics became the prime focus of most of the short films that were produced around the different dimensions of the pandemic. The author’s short feature film Covid Honeymoon (released in July 2020) was not an exception to this trend. Its central theme was a young couple who were stranded in a strange place while their hopes shattered. Literally, 95% of the shots were shot in a tiny storeroom – size that of a toilet – where they were stuck in Singapore as they could not afford a proper hotel.

The pandemic in Sri Lanka was not a mere health crisis. Rather, the pandemic was deeply enmeshed with a turbulent political environment that showed signs of authoritarianism and militarization. Hence, at the very initial stage of the spread of the virus, there was a sense of denial of the pandemic. This was due to the exigencies of holding a general election to further consolidate the power of the executive president who was elected just before the onset of the pandemic. Hence, the pandemic was politicized from a very early stage of its spread. These broader political realities and dynamics were not strongly captured in the mainstream film (Aale Corona) (released in Jan 2021) as well as other short films that portrayed different aspects and dimensions of the pandemic. Asoka Handagama, the director of the first pandemic film in Sri Lanka, Beer without Alcohol, is generally considered a director who brings in a political subtext as a basis of his films. He is acclaimed for this inclination as some of his films bagged the best direction award at film festivals held locally and overseas. However, his pandemic film took a focus on a bunch of friends who are sharing the feelings of loss, pain, and dilemmas of their respective love lives. One can say the film deals with some form of politics of love in the context of relationships. However, the broader political dynamics of the pandemic period are not significantly represented in the film.

Muvindu Binoy’s film, ‘An Overdose’, featured in the Anthology, Goodnight Colombo (released in July 2021), in a subtle way but very powerfully touches upon the extreme ethno-religious and ethno-nationalistic political ideology that was dominant during the regime of Gotabaya Rajapaksha. The short film mimics the practices of extreme beliefs bordering on superstition and witchcraft that were promoted to combat the pandemic. Such acts, for instance a syrup that was concocted by a person (with no medical training or accreditation) who claimed that the formula was revealed to him by a God in his dreams, became widely popular as a medicine to prevent or combat the virus. This syrup, which did not pass any form of medical tests or certification, was consumed by the Minister of Health together with Ministry officials and was widely seen in television and social media. The same minister was seen dropping pots of pirith paen, blessed water – that was blessed by priests with many hours of chanting – to rivers. It was believed that such acts would contain the virus. The plot of Binoy’s film involves two young men, one stuck in the house due to lockdown and the other who can travel around given his job as a delivery boy of a food outlet. The friend stuck in the house badly needed some alcohol and the delivery boy smuggled in a bottle of illicit liquor, kasippu. The friend gets high instantly, dances crazily and collapses soon afterwards to be unconscious till the next morning until the delivery boy comes. It is only then the delivery boy realizes that he had mixed up the bottle of liquor with a bottle of pirith paen, the blessed water, as they both look alike in colour. With a highly funny and sarcastic style, Binoy makes the utmost mockery of some practices that were promoted and endorsed by the government. The film laughs at the absurdity of the ethno-religious ideology that prevailed during that period.

Author’s film A Covid Honeymoon (released in July 2020), at some level, touches upon the Sri Lankan political realities and pandemic political dynamics. The drama in the film is between a young couple who came with a fairy tale wish to spend their honeymoon in Singapore which is considered the ‘wanna-be’ status of Sri Lanka’s economic progress. The film juxtaposes the political fantasy of a developing country with a dream of a young couple who comes to Singapore for their honeymoon, but their real mission is to buy a small stock of computer parts to be resold in Sri Lanka with a profit and out of that they could afford a grand wedding party later. The film also contains a part when the couple is getting intimate, a montage of political rhetoric of the Sri Lanka’s President, the Opposition Leader, other politicians, and the military is played in the audio track, mimicking the desperate and cosmetic responses made by the political leadership to fight the virus. This, towards the end of the film is contrasted with a mix of visuals of the Singaporean Prime Minister making a classic inspirational address to the nation speech while the couple was in the middle of making love. The Singaporean PM says, “Singapore has all the resources and the will to fight the pandemic” while the couple was gasping in a heightened stage of love making. The PM ends his speech with a deep sense of determination by saying “Singapore shall rise” while the woman changes her position and comes on top of the man but their close-to-climax love making act abruptly ends when they receive a call from the lodge owner to ask them to vacate the place as they have not paid even the paltry rent for a storeroom.

In a way, the pandemic gave a new lease of life for filmmakers, particularly the short film makers in Sri Lanka whose audience is different from the mainstream cinema which is based on long feature film format and distribution in conventional cinema halls. The access to online streaming platforms allowed these films to be disseminated without any cost, in most cases, and reach an audience as the online presence of people was exceptionally high during the pandemic. Moreover, due to online streaming, the outreach was not limited to Sri Lanka; large sections of Sri Lankans living abroad too became part of the audience. Meantime, the Sri Lankan filmmakers were quick to get adapted to create films under very different conditions dictated by lockdowns and social distancing regimes. As such, a new technology of production of films emerged and that knowledge was at times imparted institutionally. Hence, the Sri Lankan Pandemic Cinema ushered in a new modality of production which was characterized by resilience, adaptability, and improvisation under trying circumstances.

A Covid Honeymoon (2020), the official poster

Source: Udan Fernando

A Covid Honeymoon (2020), the Announcement of the Film Screening

Source: Goethe Institute, Colombo

Thanks

The author wishes to thank the veteran film maker Asoka Handagama and filmmaker and curator Anomaa Rajakarunaa for their comments, feedback and information given to the early drafts of this paper. The author also thanks the film directors and others who agreed to be interviewed and quoted in this paper. Finally, the author acknowledges the support and encouragement given by Prof. Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin to improve the early draft of the paper as well as the giving comments on structing the paper at the initial stage of writing.